Our time in the States seemed to fly, although when we got

there in June, we thought we had forever to enjoy life ashore. It’s always a pleasure to see family and

friends when we’re back there, but we can’t help being shocked by the contrasts

to the simple life to which we’re accustomed.

There are so many people, moving so fast. Apparently, they are all searching for

something that eludes them, because they seem never to stop. Individually, our countrymen are friendly and

kind, but our society comes across as fast-paced, uncaring, and acquisitive to

the point of obsession.

Shortly before we left on our return journey to the islands,

we went grocery shopping at a discount department store with our daughter. As she and Leslie browsed the grocery aisles,

which took up maybe 15% of the store’s space (!), I stood in the front

right-hand corner and gazed diagonally across the store. The back left-hand corner was so far away

that I couldn't make it out clearly, and I can pick out man-sized buoys at sea

at a distance of well over a mile. I was

awestruck. This one store could shelter

the entire population of some of the countries that we visit, and it was

stocked with more merchandise than the islanders could find in their whole

country. When we got back to her house,

our daughter realized she had forgotten something. “We’ll stop on the way to pick up Elise from

school,” she said. School was in a different

direction from our morning outing, and she stopped in another store of the same

chain, equally big, equally crowded, and equally well stocked. It was no more than a few miles from the one

where we had stopped earlier.

Now we’re back where the stock in even the gourmet grocery

store depends on “what de boat brought las’ time.” Life has taken on a more personal quality

again. While I got Play Actor ready to launch after her five months out of the water,

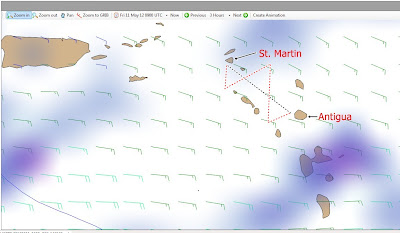

Leslie walked a couple of hundred yards from the boat yard to the government

office at Jolly Harbour to deal with Customs, Immigration, and the Port

Authority. The senior Customs officer

greeted her with a, “Welcome back, Captain.

It’s been a long time since you las’ visit.”

“You haven’t been working here for the last year or two,”

she responded.

“No. I’ve been

working at the airport. It’s good to be

back where I know the people I deal wit’.”

After she finished with the paperwork, the yard crew had the

boat back in the water and we took her out to a mooring and launched the

dinghy, returning to the yard office to settle up our account. That taken care of, we walked across the

street to the Epicurean Market to pick up some necessities, including fried

chicken for lunch.

“You have no bananas,” Leslie remarked to the cashier as she

rang us up.

“De boat from Dominica don’t bring one time. Nex’ week, mebbe so.”

We went back to Play

Actor and put up an awning. Sitting

in the shade eating our chicken, we were entertained by watching several

geckos at our feet chasing bugs. They moved aboard in our absence, apparently. When we're in residence afloat, it's a bit like living in a castle with a moat. Crawly creatures can't come to see us unless we (inadvertently) bring them aboard. We have

a whole new ecosystem now, just in our cockpit. We contemplate our new neighbors as we eat. We could do without the bugs, but the geckos are kind of cute. We decide to see if they can handle our bug problem instead of spraying with insecticide, as we usually do after taking the boat out of storage. Of course, we'll eventually have to start feeding the geckos; there aren't many bugs except ashore. Nex' week, mebbe so. It’s good to be home.